Articles

Bidlo, Danto and the Art of Absence

How can an artist’s act of erasure transcend banal expression and reveal a new language of hidden forms? How can a social catastrophe shape the work of artists and prompt them to respond with diverse kinds of expression? The negative impulse, which may originate within the artist’s psyche or in the society at large, is clearly a seminal force in the process of art making. Like winter before springtime, a snowy shroud seems to balance new growth in the arts, heightening critical awareness and promoting experimentation. The themes of loss, absence and renewal are explored very differently in two recent New York exhibitions.

Mike Bidlo: Erased de Kooning Drawings

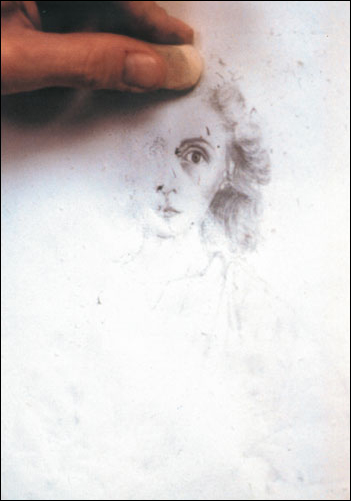

Like much of Bidlo’s oeuvre, the Erased de Kooning Drawings are based on a precedent in art history. In 1953 Robert Rauschenberg took a drawing that had been given him by Willem de Kooning and methodically erased it to a ghost of its former image. Rauschenberg then titled the work Erased de Kooning. While Rauschenberg transformed only a single piece, Bidlo has recreated and erased a series of de Kooning drawings at Francis Naumann Fine Art, ranging from portraits of Elaine de Kooning from the 1940s to his Screaming Girls of the late 1960s. While Bidlo’s past forays into appropriation have consisted of reproducing works by other artists, this exhibition is predicated on the appropriation of a gesture.

One of the most interesting things about Bidlo’s appropriations is that they are born of an almost reverential respect for the modern master being emulated. More than a conceptual project, Bidlo’s art is derived from an intimate process whereby, through immersion and imitation, he arrives at a more complete understanding and appreciation of his modern mentor. That said, he has lately appropriated the work of artists who have challenged traditional notions of aesthetics and art making with a Dadaist edge (Marcel Duchamp, Yves Klein and Andy Warhol). Therefore the choice of Robert Rauschenberg’s seeming obliteration of a de Kooning drawing reflects Bidlo’s conflicted relationship with Modern Art (other Bidlo patriarchs have included such expressive artists as Edouard Manet, Fernand Léger, Pablo Piccaso and Jackson Pollock).

Another layer of meaning in this work involves the cancellation of controversial images of women. Drawn with sometimes violent gestures and angulation, the works drew criticism for a perceived misogyny. The act of erasure seems to eliminate de Kooning’s aggression toward the fairer sex. To my knowledge Bidlo has never emulated a woman artist, but has often explored the female nude through the filter of male artistic sensibilities. The neutralizing act of erasure perhaps reflects a turning point in art, in which women fluxus, pop and conceptual artists emerged as both seers and subjects, transforming and enriching artistic production from post-war years to the present day.

But then there are the erased drawings themselves. Are they truly erased? Not at all. They suffer a sea change into the coral and pearls of richly varied whiteness. They are ghost images, revealing their erstwhile subject only to the patient scrutiny of those who seek it out. Transformed by the eraser, these drawing acquire a mysterious subtlety that they formerly lacked. Together with the Erased de Kooning Drawings, Bidlo exhibits the erasures themselves, enshrined in vitrines. They seem almost like ashes, serving as the vehicle from which the white drawings resurrected themselves, phoenix-like, beneath Bidlo’s gaze.

Arthur Danto: The Art of 9/11

Theodore Adorno once remarked, “To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric.” In the face of war, murder and particularly genocide, artists do find themselves adrift. The scale of mass destruction seems to dwarf all else in sight. But while Adorno’s remark is understandable, many concentration camp survivors responded to this dark time specifically through the act of art making. Perhaps it represented a way to overcome the abasement of personal experiences or a spiritual purification marking one’s slow return into human society.

For many downtown New Yorkers, 9/11 represented a first personal encounter with the destructive savagery, devastation and chaos of war. I witnessed the World Trade Center conflagration from the roof of an East Village tenement building that had been my studio at the time. Intense flames, like furnace fire, mesmerized me, implacably swathing the black hole through which a plane struck the north tower. I couldn’t appreciate at the time that what seemed like falling debris from the building were actually human beings who had cast themselves to their death rather than endure the other fate that awaited them.

My wife Francine and I volunteered that night to help emergency personnel at the improvised Greenwich Street morgue. Hundreds of stretchers and body bags lay in wait for bodies that never came. The fires still burned too hot for firefighters to approach Ground Zero. As the rescue mission progressed, Francine worked as a volunteer in the Pit of Ground Zero among EMT workers and firemen. We lived out the months that followed below three military checkpoints in our Tribeca home. The World Trade Center that once soared before our front window, its red antenna blinking through the night, had become a smoking pyre. First ash and later smoke polluted our home. The acrid smell of burning bodies, diesel fuel, and the pulverized buildings filled our nostrils while fighter planes and helicopters watched over our sleepless nights.

One of the many effects that this tragedy had upon me was a complete creative paralysis. I had a book contract with deadlines but I couldn’t bring myself to write. In my studio I listened to radio reports and reflected on the suffering around me, but was unable to make art. In reading Arthur Danto’s essay for The Art of 9.11 at Apex Art, I was most intrigued with the way he describes the makeshift altars that took form all over New York City and particularly in lower Manhattan, as an act of artistic expression.

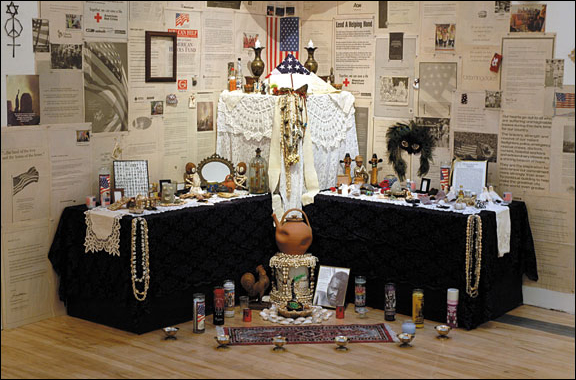

Danto’s point is well taken. These memorials to the dead reflected a reawakening of the humane, empathic and creative forces of New Yorkers. They had an iconic potency, reflecting the communal grief in which all citizens shared. New York City Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe recently spoke to the manner in which people sought out the company of others in parks after 9.11 and the way so many shrines were produced at Union Square that they had to be removed and transferred to the city archive. I also remember that schoolchildren from around the country sent drawings to New York City after the attacks. Some were affixed to a chain link fence on Canal Street, between 6th Avenue and Hudson. Along the fence I was taken with one such drawing realized by a Spanish speaking child in California who had drawn the twin towers in the sky above New York, enfolded within the protective arms of the Virgin Mary. At the time it moved me to tears.

The Art of 9/11 was curated in a way to include a group of Arthur Danto’s artist friends, who each exhibited a work or works related to the tragedy. Leslie King-Hammond’s Prayer for the New Ancestors: Altar for the Warrior Spirits of 9/11, Lucio Pozzi’s Nothing #5 September 11, 2001 and Barbara Westman’s Memory Piece were all works that one might visually associate with the event. Pieces by the other seven artists in the show had a more oblique relationship to 9/11, reflecting personal iconographies. Each artwork was exhibited together with a text by the artist which described his or her experiences on 9/11 and how the work was arrived at.

Danto’s approach, allowing each artist tell his or her story, was very effective. Cindy Sherman exhibited a photograph of herself as a clown, the source of primal childhood fear, while Robert Rahway Zakanitch showed paintings of lace, which he regards as a symbol of the interconnectedness of human destiny. On the evening of the attacks Audrey Flack simply painted boats at twilight at Montauk harbor. It was the only meaningful response she could muster in the face of such destruction.

9/11 was a watershed event in American history and no single exhibition could fully address its meaning and complexity. Nonetheless, Arthur Danto’s Art of 9/11 provides a thoughtful exploration of unifying power of art despite myriad interpretations and expressions. Indeed, the exhibition’s very strength lies in its fragmentation. 9/11 represented terrible losses of human life and the destruction of an architectural icon, but from this absence also came meaningful self-examination and personal transformation through the act of art.

Mike Bidlo: Erased de Kooning Drawings, Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, 22 East 80th St., to Nov. 11, 2005

The Art of 9/11 Curated by Arthur C. Danto, Apex Art, 291 Church Street, to October 15, 2005

© 2005 Daniel Rothbart. All rights reserved.