The Floating Art World: Alexandra Munroe On Mariko Mori, Takashi Murakami, Yoko Ono, and Japan

Japan Society Gallery Director and renowned curator Alexandra Munroe recently spoke with Daniel Rothbart about the influence of Japanese culture on recent work by Mariko Mori, Takashi Murakami, and Yoko Ono.

***

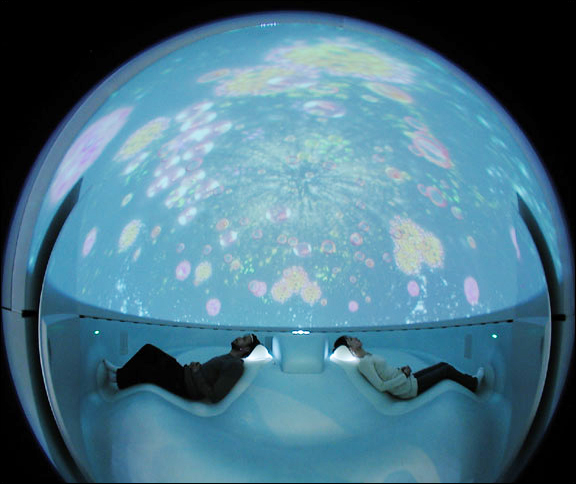

DKR – Mariko Mori’s Wave UFO project was realized on the premise that three anonymous people, lying in the same enclosed space could create a work of art through the interaction of their brainwaves. The lily pad shaped stair leading to the vessel and imagery in her animation seem to allude to icons of Buddhist art. Might you comment on Mori’s marriage of Conceptual Art, technology, and Buddhism?

AM – Mariko Mori’s conception and realization of Wave UFO represents an altogether new art form for which no name yet exists. It is sculpture, installation, design, performance art, live media, bio-technology and even car design: the skin of the vessel is made by Lamborghini car manufacturers yet exhibits an opalesque surface that recalls the finest sixteenth century Nashiji lacquer techniques. Her ability to freely extract from such radically diverse references – traditional Japanese aesthetics, cutting-edge media and the mind of contemporary culture – to create a vision as original and precisely realized as Wave UFO suggests, to me, a certain creative genius. Bio-interactive art emerged in the late 1980s, when Japanese, European, and American artists associated with Canon Art Lab in Tokyo developed ideas in which brain waves and bodily interaction were harnessed to the making and practice of new media. Mariko draws on this recent technology that Japan excelled in. But she is drawing too upon very profound ideas that she has grasped and interpreted – or creatively misinterpreted – from her recent studies of Buddhist art and thought; most obviously, the concept of oneness. In Wave UFO, she aims to provoke and induce a state that is akin to a Buddhist state of enlightenment or of oneness, a kind of atman state. And you’re absolutely right – Mariko uses specific iconographic motifs in Buddhist art and thought to her own ends. For example, the lotus flower, emblem of the purity and perfection of mind that we are capable of attaining although our beginnings are rooted in muck – common existence composed of our sufferings, desires, the burden of karma. Mariko is an artist who looks at tradition as an inventory of forms and ideas. From this inventory she adapts and extracts images for her use, giving them a different color and substance, casting them in a different medium, yet updating the underlying meaning of what that experience of the traditional art form or spiritual idea is.

DKR – Manga and animation exert a strong influence on the work of Mariko Mori and Takashi Murakami. Does manga constitute an escapist vent from the hierarchies of Japanese society?

AM – The whole world of manga and animé in Japan constitutes a mega industry. Well over 50% of books published in Japan each year are adult manga. Throughout Japan you are constantly bombarded with images derived from manga or animé, whether at the shopping arcade, the train station, the vending machine, or walking along any major thoroughfare. So much of the advertising, commodities, and gadgetry that define visual culture in Japan are rooted in what I call the “culture of kawai ” or the “culture of cute.” Japanese society exhibits a perverse fascination with childlike forms, cuteness, happy faces (like Mickey Mouse). And it doesn’t pervade the visual culture only: Cute, babying voices greet you over the intercom at every juncture of your movement through, and use of, Japanese commercial and public spaces. The voices compliment the mothering cuteness and safety blanket images that bombard Japanese visual culture. I can’t explain the origins of this phenomenon but I have observed it become stronger over the last decade, and now the dominant language in Japanese visual culture is the cartoon figure. As you suggest, manga and animé could represent an escapist tendency. But it has become so dominant that you actually need a mechanism to escape from it. It’s the lingua franca of Japan now, this culture of the cartoon. Japan has never been very interested in empirical reality. Both traditional and modern Japanese art are most comfortable in a supra-real, surreal, or conceptual space. Western culture is rooted in the here and now, scorns escapism and fantasy, and makes adults feel guilty about “play.” In Japan, there is license for that type of thinking. If you look at the tradition of poetry, it is always nuanced and unclear whether its experience belongs to this world or another world. Manga and animé are a new incarnation of this Japanese cultural thinking. There is a great tolerance in Japan for the bizarre and the grotesque, and several movements in Japanese avant-garde art, including the work of Yayoi Kusama, Butoh dance, Tomio Miki, and Testumi Kudo, are rooted in a fascination with sex, madness, death and the grotesque. In Japan, the grotesque and the cute are deeply related, one the inverted manifestation of the other. In both cases, there is a tolerance for the edge of reality, for bizarre distortion. It does not represent an escape from reality; the Japanese are just wired for it.

DKR – Yoko Ono’s work is infused with a sense of social responsibility while the younger generation of artists is less political. Murakami, in a recent interview, commented that most Japanese people suffer from political apathy. How do you view the role of politics in Japanese contemporary art?

AM – The 1950s and ‘60s were an enormously radical period in Japan centered around anti-nuclear, anti-US, and anti-establishment movements. A number of artists of the 1950s and ‘60s were revolutionaries who were seeking in art to launch a social and political critique of the status quo, such as the Neo Dada Organizers, Hi Red Center and the VIVO photographers. I agree with Murakami that artists in Japan are less political today than during the postwar period. Of course, several artists emerged in the 1990s waving various “politically correct” flags, exploring themes that have been particularly trendy in European and American art, including race and gender topics. These efforts can be understood more as a response to international art movements and critical theories than as a radical critique of the unique conditions of contemporary Japan. Thus I agree with Murakami that today’s Japanese artists are not very political. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing; art doesn’t need to be political to be good. For example, Yayoi Kusama is one of the most important Japanese artists of the 20th century, yet the best of her work is not overtly political. Her art is great because it gives form to sublime and terrifying psychic realities. Neither is Yoko Ono’s art strictly political. Her work is aimed more at a shift of consciousness, a social transformation achieved through personal transformation that happens when the viewer participates in a work of her art.

DKR – You once commented that one of the most Eastern qualities of Yoko Ono’s work is her use of language. How would you describe the relationship between her instructions, Matsuo Basho, and the tradition of Japanese poetry?

AM – Yoko Ono’s use of language is central to her art in all media. Almost always, there is a component or element of language in her art whether a song, a performance piece with an instruction, an object that has an instruction inscribed on its pedestal, or an installation that has a participation instruction that is part of the piece. I like to think that her work is essentially poetic in the sense that it is not didactic, is very abstract, and operates on a conceptual level—inviting us to a kind of interior dialogue. It’s not simply about looking at art and experiencing a specific work. It’s about jolting us into an interior recognition of ourselves which in turn shifts our consciousness. Her work lies in that shift. It is very akin to the tradition of poetry in Japan, especially haiku, a poetry in which the image triggers insight. In Yoko’s approach to poetic language, she draws as well upon the East Asian literati painting tradition, wherein landscapes are conceived as “landscapes of the mind.” In the West we have a landscape tradition that aims to be a substitution for reality, that tricks us by its realism into believing that we are peering out a window. In East Asia, where landscape painting is often accompanied by a poetic inscription, it functions as concept, not illusion. It is the mind of the artist that you’re being invited to commune with rather than a contemplation of an image of nature as a signifier of the real. Japanese art is rarely a signifier of the real. It is a signifier of a conceptual place that is richly resonant with literary, historical, cultural, and philosophical associations. Yoko’s art, consciously or not, is linked to such an approach.

DKR – Yoko Ono’s project for the “Snow Show” at the Venice Biennale this year is a jail made of ice. Could there be traditional influences on her latest project?

AM – I have not heard about this project but it sounds wonderful. What strikes me as essentially Japanese about this new work is its condition of transience. Yoko posits an image of something as hard and permanent as architecture, and as closed and confining a conceptual form as a jail, and then has it melt into something that is wide open and returns itself to nature. The jail becomes something that is neither hard nor manmade nor architectural, nor confining. The inversion is so fantastic. It’s so perfectly Yoko! She completely upends and literally dissolves the concept of jail—and so frees those prisoners or imprisoning ideas we hold in our hearts. Her strategic attack on your brain works to free you up. Yoko’s artistic brilliance lies in that kind operation. It is like a Zen koan—thinking the improbable gets your mind to leap to a place of new mental and conceptual possibilities.

© 2003 Daniel Rothbart. All rights reserved.