Robert Morgan’s Purgation of Nike

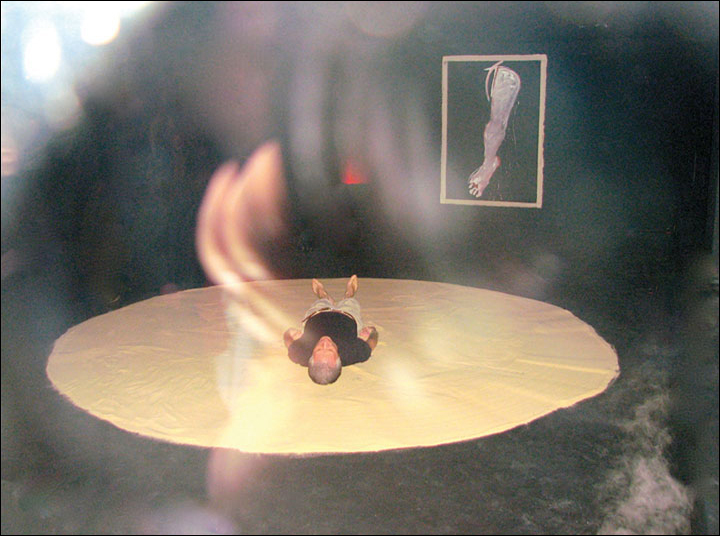

It is twilight outside the Lab Gallery in midtown Manhattan. I join a group of art aficionados and curious passers-by who peer through the gallery’s glass façade, at a large circle of sand, illuminated from above by a spotlight. In the foreground is a bucket of steaming water and against the far wall leans a broom with a warped handle. A video monitor perched on a stand in the corner pipes real-time images of the gallery. On the wall is a painting of what seems to be a disembodied leg. From speakers outside the gallery we hear deep, low chants, which I discover from the press release are a slowed-down voice recording of the artist reading a swim manual from the 1930s. The spotlight goes dark and when it fades back on, a barefoot man is lying barefoot on his back in the sand.

The man is Robert Morgan. A prolific artist and scholar, Morgan has, for most of his life, engaged in experimental, avant-garde discourse from the vantage point of both practitioner and critic. His hands begin to move as he counts his fingers and gestures toward the painting of a leg. The light recedes again and when it is newly illuminated, Morgan stands outside the circle. He circumambulates the mound of sand, steps inside, and circumscribes four smaller circles around his body with his hands. Are they the four directions? Like the Vitruvian man, he interacts with the geometry as an extension of his own body, marking it with his hands and traversing it with his feet. Like a shaman he takes water in his mouth and spits it onto the sand, turning it to red clay. Then he steps outside the circle, and leans against the wall beside the broom.

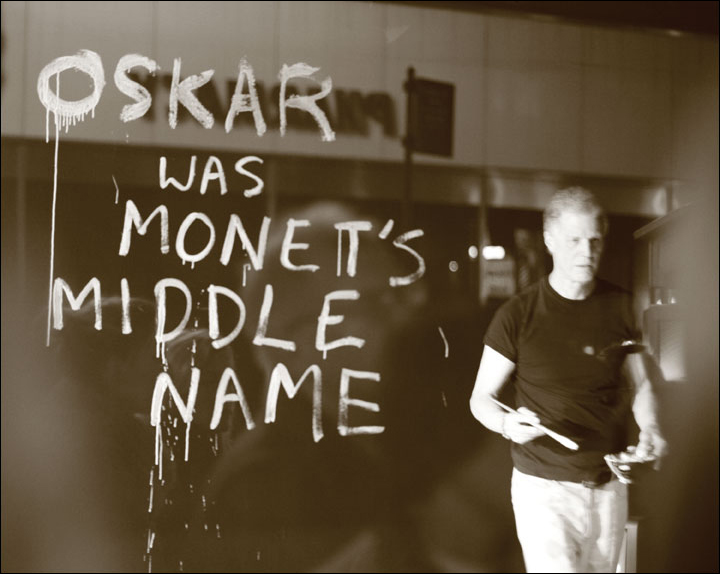

Morgan mixes white paint with water and begins to write on the black walls of the gallery. Chinese and Korean ideograms emerge along with “Oskar was Monet’s middle name,” written in English. The artist returns to the sand where he digs up a coin. After cleaning it with his hand, he shows it to the public beyond the window. Once again, he digs in the sand, this time producing a condom, which he shares in mime dialogue with women viewers through the window. Morgan inflates the prophylactic like a balloon, writes his name on it, and throws it onto the sand. He writes, mujima, or, “don’t tell” in Korean with paint on the wall. Taking the broom, the artist sweeps around the edge of the circle and traces a Mesopotamian sun sign with his hands in the sand, squaring the circle. The light dies down and when it reemerges, Morgan once again lies supine in the sand. He gestures toward the leg and the light fades to black. Gradually the chanting concludes and noises of midtown reclaim our senses.

The painting of a leg, like chants from a swim manual, slowed just to the point at which we cannot discern words, embody Morgan’s belief that language conceals intention. Conflicting signs and disjuncture abound, like the assertion of Oskar, the German name a man commonly believed to be the quintessentially French impressionist. Spanning time from prehistory to present and language from east to west, Morgan exposes the ultimate subjectivity of systems we commonly take for granted. Despite Nike’s western provenance, and clear Vitruvian references, this performance seems primarily grounded in eastern philosophy. Like Buddhist mandalas, Morgan’s circle is the locus of meditation, but a meditation on art, language, communication, abstraction and the nature of worldly aspirations, commerce and sense pleasures. It feels as though the artist has taken us on journey through different states of consciousness, arriving at the same place where we began but wiser for it.

© 2009 Daniel Rothbart. All rights reserved.