Personalizing a Vast Human Tragedy: The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

On a recent trip to Washington D.C. I visited the National Holocaust Museum. On passing through its limestone threshold I was greeted by a rather intense looking sharpshooter with a microphone in one ear and a drawn pistol in his hands along with the requisite x-ray machine and security guards. Visually it was an abrupt transition from the Neo-Classical façade to an industrial architecture of bricks, triangulated steel girders, and plate glass. Above me, on either side, were structures reminiscent of guard towers and natural light poured in through a canopy of glass overhead. Despite his beneficent purpose, the sharpshooter’s presence contributed to an atmosphere of discomfort. Ticket in hand, I proceeded to the elevator. It was flanked by a table on which two baskets were laid out, each containing hundreds of leaflets resembling passports, one basket labeled “men” and the other “women.” I took a man’s passport.

Nazi Assault – 1933 to 1939 (Fourth Floor)

I exited the elevator onto the fourth floor which documents the Nazi rise to power and the state religion of militancy, conformity, nationalism, and antisemitism. As Walter Benjamin once noted, the Third Reich attained popular support by transforming politics into art or at least spectacle (Leni Riefenstahl’s footage of the Nuremberg Rallies comes to mind). But the artifacts on display tell a lurid story of institutionalized racism that was adopted by millions of ordinary Germans. What stand out particularly in my mind are swatches of human hair of different colors and glass eyeballs used to calibrate the level of a subject’s racial purity. Particularly moving were large-scale photographs of “mixed race” couples who were forced to wear placards describing their transgressions in public places. Between photographs and artifacts, curators create a sense of the social conditions and propaganda tools which enabled Nazis to demonize Jews, Gypsies, communists, and homosexuals. National Socialist children’s books drive home a sense of the ease with which a corrupt state primes and conditions the values of its citizenry.

Passport in Life

Page one of my passport revealed the identity of Wilhelm Kusseroh, a gentle looking young Jehovah’s Witness from Bochum, Germany. Jehovah’s Witnesses were persecuted by the Nazis for their allegiance to God over Hitler, and Bochum’s home was repeatedly searched by the Gestapo and religious material confiscated. The Bochum’s held Bible study meetings in their home despite the fact that Wilhelm’s father had been arrested twice. I was instructed to read further on concluding my visit to the third floor.

The Final Solution – 1940 to 1943 (Third Floor)

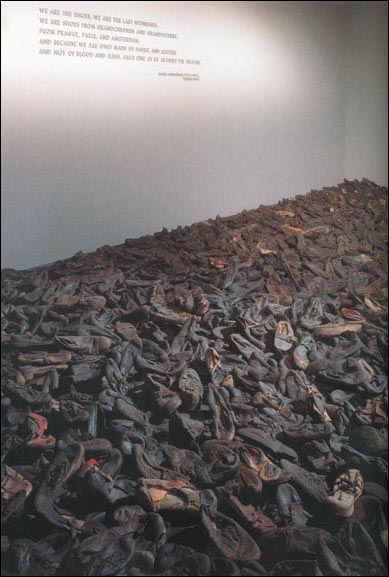

I descended to the third floor which documents the mechanization of murder. We are all so used to seeing atrocities committed on the evening news that it is sometimes difficult to appreciate the gravity of a crime and empathize with its victims. But exhibition designers succeed in the delicate task of conveying both the magnitude and personal tragedy of the holocaust through the use of artifacts. One of the most disturbing relics is a railway car that was actually used for deportations on rails that once led to Treblinka Concentration Camp (it was a gift from the Polish government to the museum). You have to pass through its two open side doors to move from one part of the exhibition to the other. Once inside it is not difficult to imagine the fear of passengers in this lightless boxcar, without food or water, and amid rumors of the fate that awaited them. Another powerful exhibition is a floor installation of thousands of shoes of victims from Majdanek Concentration Camp near Lublin, Poland. Somehow the women’s shoes were particularly disturbing as they more closely resembled the personalities of their wearers. Another exhibit that I found moving included actual trees from Rudniki Forest, Lithuania, where Jewish partisans fought the Nazis. These objects and timber seem unlikely survivors of all this suffering, but in real terms they held greater value to the Nazis than thousands of human lives.

Passport in Death

After war broke out, Wilhelm Kusseroh refused to be inducted into the army citing the sixth commandment of the Decalogue “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” He was sentenced to death in 1940, although the court offered to rescind his execution if he would renounce his “evil and destructive beliefs.” Wilhelm Kusseroh was shot by a firing squad in Muenster Prison on April 27, 1940. His defense counsel stated Wilhelm “died in accordance with his convictions.”

Art in the Holocaust Museum

Minimalist paintings by Ellsworth Kelly and Sol Lewitt are featured in mezzanines between the third and fourth and second and third floors. They are strong pieces, and under different circumstances would have spoken to me, but they seem superfluous to the holocaust exhibits. Architect James Ingo Freed views these pieces as loci for attention and reflection between exhibitions but their language of abstraction lacks the presence to coexist with holocaust artifacts. More successful were two sculptural projects; Gravity by Richard Serra and Loss and Regeneration by Joel Shapiro. Serra’s Gravity is a twelve-foot square slab of steel that weighs nearly thirty tons, cutting into stairs in the Hall of Witness to form an oblique barrier to visitors climbing or descending the steps. It speaks of separation of the living from the dead, and creates a necessary discord in the otherwise classically-inspired architecture of the Hall of Witness. Joel Shapiro’s Loss and Regeneration, a monumental work in two parts, is dedicated to the children who perished in the holocaust. Sited outdoors, the work consists of an overturned house and approximately 100 feet away, a stylized tree. Shapiro views the house as representing, “security, comfort, and continuity” while the tree is emblematic of renewal following the tragedy. The artist accompanies his work with an excerpt from a poem written by a child in the Terezin Ghetto in Czechoslovakia:

Until, after a

long, long time,

I’d be well again.

Then I’d like to live

And go back home again.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is located at 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW, Washington DC 20024, www.ushmm.org, 202-488-0400.