Gillo Pontecorvo’s Wide Blue Road

Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò and The Battle of Algiers were films that changed the course of political cinema by way of their artistry and psychological complexity. Unlike filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Roberto Rossellini, who sought to dehumanize political adversaries, Pontecorvo embraced the complexity of situations and human relationships. Pontecorvo’s own experiences as a partisan during the Second World War helped to shape his appreciation of human behavior under difficult circumstances. Kapò, Gillo Pontecorvo’s second feature film, examines the life of Edith, a young Jewish girl from Paris who is deported to a German death camp and chooses to become a Nazi appointed camp guard or Kapò in order to ensure her survival. Edith is beaten down and acculturated by the Nazis, but ultimately redeems herself by a gesture of self-sacrifice. The Battle of Algiers, Pontecorvo’s third feature film, recounts the guerrilla incidents of 1957 that ultimately led to a French colonial withdrawal from Algeria. While endorsing the Algerian people’s right to self-determination, Pontecorvo even handedly depicts the suffering and fear of everyday French pied noirs, who are victims of urban terrorism. French youth dance to the music of a juke box, families relax in a bistro, and travelers wait in the airport moments before their lives are cut short by FLN bombs. Pontecorvo’s protagonists buy progress at a dear price.

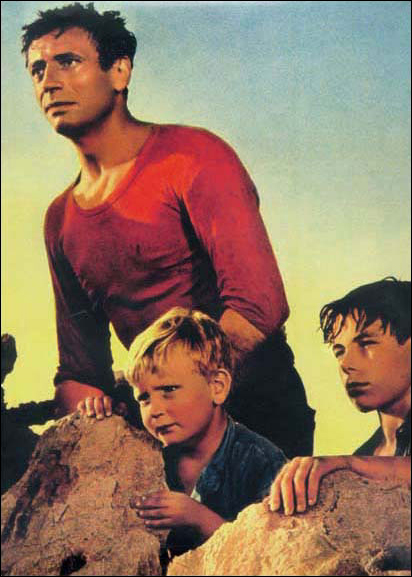

Through the efforts of Jonathan Demme, Dustin Hoffman, and Milestone Films, Pontecorvo’s first film The Wide Blue Road, has now become available to American audiences. It tells the story of Squarciò, a fisherman of the Dalmatian Islands (present day Croatia) who manages to eke out a slightly better living than his compatriots by detonating underwater explosive charges, an illegal practice that kills large numbers of fish. Squarciò fishes with his two admiring sons, who he teaches to swim and fish. Squarciò detonates his charges on the open sea, while other fishermen work near shore with nets. Squarciò sells sea-bream rather than sardines, and is not touched by the difficulties of other fishermen who sell common fish to an exploitative wholesaler. The sardine fishermen, led by Salvatore, organize a fisherman’s cooperative, and plan to buy a refrigerator that will enable them to sell fish directly on the mainland. When a new coast guard official is appointed to patrol the Dalmatian Islands, Squarciò is forced to sink his boat while fishing with explosives, to avoid capture. Squarciò then begins to fish near shore, moving him into direct conflict with the other fishermen. These trials bring about a painful coming of age for Squarciò’s sons, who, for the first time, view the selfish side of their father.

Yves Montand, superlative anti-hero of Wages of Fear, interprets the Dalmatian fisherman with great pathos. Squarciò, who’s fishing boat is christened Speranza (hope), once sought to lift his family out of poverty, but his personal ambition extends to outfitting a refrigerated trawler and fishing with his sons in faraway lands. He is charismatic, and at one point, early in the film, uses his influence on the wholesaler to negotiate higher pay for the sardine fishermen. He loves his wife and family dearly, and seeks to provide for them in the best way he can. He has debts to pay off and a daughter’s dowry to raise, however, and he loses sight of other people’s needs. Squarciò’s wife would like for him to settle down to net fishing, fearful every time he goes out to fish that he may be arrested or, worse, injured by his own explosives. Squarciò’s daughter is courted by two young men who, in different ways, fall victim to Sqarciò’s designs. The first is killed in an explosion when he tries to adopt Squarciò’s livelihood as a dynamite fisherman and the other, Salvatore’s son, is forbidden to see her after Squarciò makes a crooked business deal with the fish wholesaler. Finally, Squarciò is fatally injured in an explosion while fishing with his two sons. He admonishes his youngest son, upon his death, to set things right and join the fisherman’s cooperative.

The Wide Blue Road is, like all of Pontecorvo’s production, beautifully crafted. Seagulls become a leitmotif from the opening credits, in which the camera follows a lone bird flying in the sky. Before the credits are over, the camera frames a flock of seagulls and follows their flight until they land on the glistening Adriatic. The seagulls appear again during the film as a visual metaphor of the cooperative’s fleet of fishing boats, and a flock of seagulls is the last thing that Squarciò sees, as he lies mortally wounded on his own tiny islet gazing into the sky. Gillo Pontecorvo studied music before becoming a filmmaker, and the haunting folk songs he chose for The Wide Blue Road reflect soulful, timeless rhythms of life in a fishing village. After a successful catch, Squarciò brings his family an American radio as a gift (While Milan was being bombed by the English, Pontecorvo entered a flaming apartment to rescue his recording machine.) On it they play American Jazz, and it becomes an object of fascination for Squarciò’s youngest child. Guitar music frames a lyrical sequence of fishing boats that return home at night and a scene in which Squarciò drinks with compatriot dynamite fishermen. Some of the most vivid episodes of The Wide Blue Road can be found in seemingly incidental music and cinematography.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2001.