Excerpts from an Interview with Keith Sonnier

DKR – How did bayou culture influence the development of your work?

KS – I think that when you come from a regional part of America and you spend a long time in that area, whether you’re from the west or the deep south, or New England, you are influenced by nature, the people you grow up with, and the culture of the place. Growing up in south Louisiana with its strong sense of identity and Cajun language base was very interesting. The culture with its cuisine, music, and literature is very strong although there is no visual arts tradition to speak of. Music and cuisine were then as they are today the strongest forms of expression. When I go home I still get lots of ideas, particularly from the landscape. I am so moved by the landscape, its extremely melancholy in the winter.

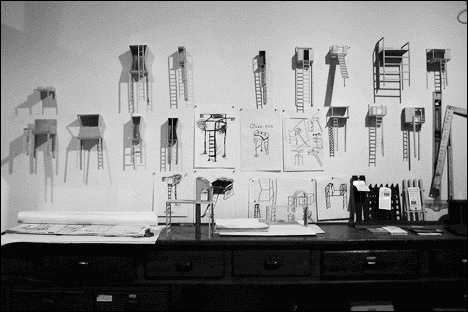

DKR – I was thinking of the elevated structures in your studio and their relationship to traditional architecture in Louisiana.

KS – Well you know there is a lot of architecture in Louisiana that is on legs because of high water, and even my grandparent’s house is on legs because of climate changes and to make it cooler. My interest in pulling the architecture up comes from an anthropomorphic source too, as opposed to sculpture that’s on a pedestal.

DKR – Which artists were early influences and which artists hold the most interest for you today?

KS – I came to New York at a very unique time. There was a real dialogue between artists. People talked about work, not about how much money they made or how their prices were. A lot of different work and movements happened in a period of ten years, from Abstract Expressionism to Pop and Minimalism and one sandwiched right into the other. It was a very interesting time to be in New York and I must say I embraced New York when I first came here, I was so happy to be out of the country, and just to see contemporary art on such a large scale. Joseph Kosuth, Richard Serra, and I along with many other artists spent time together. We travelled and spent time with artists on the west coast and in Europe. A lot of us showed in Europe before we showed in New York, I showed in Germany before I showed in New York and Richard (Serra) showed in Italy before he showed in New York. A number of us had had some European exposure.

DKR – What kind of a dialogue existed between you and other artists working with light?

KS – There was very little dialogue about working with light when I was a younger artist. The only other artist who worked intensely with light was Bruce Nauman and he was on the west coast and worked with a lot of other materials too. There was Flavin, but I had very little contact with Flavin. Even though we were in the same gallery there was very little contact and we took very different approaches to working with the material. I actually had more contact with artists who worked with light in Europe, and the Arte Povera artists used light in a very sparing way. Mario Merz and Pier Paolo Calzolari and many others had a phenomenological attitude towards work. I was interested in sequence and timing early on because I came from a reductive art tradition. When I used light it was in a sequential way, that is it went on and off but in a very simple, waltz-time situation. Very early on I realized that light was an extruded material and I used a lot of extruded materials, you know that come in eight feet, ten feet, twelve feet, and come in that color. Flourescent and neon light are materials that come off the assembly line and I began to use them in these architectural or pre-architectural situations.

DKR – It strikes me that there is a lyrical quality to the new work and that neon offers you more gestural possibilities.

KS – I was never interested in neon the way Joseph (Kosuth) or Bruce (Nauman) used them, that is in text form. I was always interested in the gestural qualities of light. With neon you can actually do gestural drawing or writing. Neon is about writing with the whole body. The new works are very much about gesture and its hard to make these works technically because when they move out into space they have to be supported, otherwise they will break. They need an architectural support.

DKR – What happened to you in India?

KS – At a time when I think art in America was so convinced about its modernism I took some of my first trips to India. It was a very good education for me because it grounded me very quickly to see a culture where the physical realities of life are pressed much closer than we see them here. Art in India gets used to death. Temples are used and sculptures are anointed and that had a big influence on me. Art in this country has an iconographic quality, you know, its on the wall and you’re here. Maybe this comes from the church or synagogue but we do have that distancing in the west that they don’t have in Asian countries. India helped me to appreciate the role of the artist in culture and how one sustains creative energy.

DKR – How do the technical and precise aspects of architecture inform your work?

KS – Well I think I’m only now beginning to address that in the sculpture, because I have been working with commissioned work for ten years. In the early work light was used to define or color volumes in the architecture. Now I’m trying to address real architectural principles, like how the forms are attached and the kinds of spaces they assume. I would like to build things now. I would like to design structures. I think the earlier pieces, the standing pieces, are very much about that because they are like single occupancy dwellings in a funny way, even if they’re only to stand up in, maybe a form of torture.

DKR – How did you get involved in public works commissions and particularly airport commissions?

KS – The first public piece was done here in New York at the Seagrams building and it was such a shock. I had designed the piece and was very happy with it but as soon as I saw it in the architecture with the furniture I was so disappointed. The furniture was horrible, and it kind of detracted from the piece I felt. As I became more sophisticated and familiar with the housing of indoor work and as I began to install work in architecture as it was being built, the work changed completely. The work could be built into the architecture and that was the big change. I could cover huge areas of space and that’s what led to the airport work, because I could deal with a kilometer long space. When you make a sculpture you’re dealing with a contained volume but for what in airports are referred to as the sterile corridors, which are corridors that are miles long, you have to make sculptural works in which you can’t see the beginning or the end. I started to design work in a very different way and I became involved in musical ideas of repetition and form in designing for those long spaces. That’s how the Munich airport project was designed. Now I am working on an airport project out of doors, in Kansas City, that will involve water and light. We haven’t come to contract yet but we are on the point of coming to contract. I’m thrilled about being able to work outdoors and water is a new material for me. Around the airport there are five lakes that are water holding lakes and this water has to be airated because there is jet fuel seepage in the water, so I want to design a series of water airation units that deal with light as well.

DKR – Do you find yourself embroiled in the bureaucratic side of public projects?

KS: It’s part of the package and sometimes its bad and sometimes its worse. Sometimes you say forget it, you know, I’m not going to do it.

DKR: Explain the collaboration that occurs between architects, engineers, city planners, and contractors necessary for the realization of your work?

KS – At its best the artist and architect have a clear understanding of the meaning of the public work to the architecture. The architect must understand that the artist does not want art to be decoration. Architects used to feel threatened by public art but things are changing. Embellishing the architecture with art is the wrong approach. The art has to have a true place within the architectural setting. It can’t be put in the corner somewhere, it can’t function that way, otherwise it ends up being decoration. Engineers and planners are both crucial to making the sculpture fit in the public place. I’m not talking about the question, “is it art or not.” Unfortunately a lot of city planners get into that and I think it should be avoided at all cost.

DKR – What does your forthcoming exhibition at Marlborough represent to you?

KS – This is the first time that I have tried to combine public work that I have been doing over the past ten years with work that originates in the studio. I am making some works that are not complete but rather in a model state. Its about working in that gap between architecture and art. I don’t know if it will be successful or not, but it is something that I have been wanting to try.

DKR – What are your plans for the next fifteen years, I understand that you are creating a foundation on your family land in Louisiana?

KS – I don’t want only to be east-coast-oriented as I get older. I would also like to make works in nature and that’s a good reason to be out there. The land is affordable and there’s a different approach to working. The reason for the foundation is to encourage other artists to come. They would create a community and I would participate in a dialogue with them. I’m from a very unique little Francophile town and I think it would be very interesting to have artists in this community. They would be invited and would perform one public service, perhaps a lecture to the town, or if they were a performing artist they would perform for the town, or if they were architects they might design a structure that would be built for the community. I want to establish a dialogue beween people of Louisiana and the visual arts. Mainly the dialogue exists in music, food, and writing, but not in the visual arts. I am very interested in architecture and would like to design and build some structures and I would like to work with architects. Its not affordable in Long Island, where my digs are here, and its too sophisticated in a funny way. It needs a rougher edge. I hope it can happen.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2000.