Chinese Whispers: An Art of Displaced Perception

Chinese Whispers is a curatorial survey of Eastern European artists whose work involves issues of miscommunication. The disintegration of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Block have precipitated widespread identity crises amongst its various cultures and ethnicities. A number of artists in this exhibition hail from the former Yugoslavia, where ancestral blood feuds have resurfaced in the form of civil war. The displacement of ideology and social infrastructure, economic hardship, and violence have led to an aesthetic of the absurd which manifests itself in various ways through photography, video projects, and installation work.

Roman Ondák, an artist from Bratislava, exhibits a series of postcards entitled Antinomads. Ondák’s postcards depict people in personal environments such as a university professor in his study or a little girl in her room. The professor sits before a massive bookcase which is unable to absorb the vast assortment of periodicals and tomes which are stacked in piles at his feet. The little girl sits upright on her bed. She wears a t-shirt with a Western cartoon character and sits before curtain, which ostensibly covers a window but seems more like the sort which might cover the proscenium of a stage. A long shelf spans the top of the curtain along which her stuffed animals are displayed. Both subjects remain rooted in their place, having created a nest that reflect personal interests, house fetish objects, and reflect subtle particularities of the culture to which they appertain which are most difficult to describe and doubtless misinterpreted.

Vlado Martek

exhibits a big red map on a black ground. His map describes the immediately

recognizable silhouette of the United States, but on its face is scrawled

“Balkan” in white lettering. Where prominent American cities might

lie, the names of Balkan towns are written in black type. What does it mean? Is

it about red blood or red communism or coca colonialism or mounting racial

tension in the United States? Perhaps it reflects the almost meaningless,

arbitrary nature of cartography and alludes to the danger of false boundaries

and frontiers. Martek’s work, like that of Ondák, suggests a multiplicity of

meanings to the Western viewer. Nonetheless, an informed reading of Martek’s

map seems bound to a knowledge of Balkan history and its quagmire of separatist

movements and blood feuds.

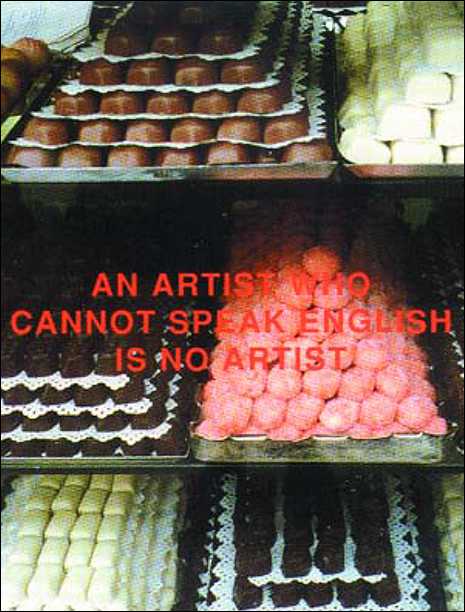

Mladen Stilinovi exhibits a print that depicts an appetizing assortment of

cakes, torts, chocolates, and marzipans, presumably photographed through the

window of a candy store. Superimposed on this image, in red type, is the

phrase, “An Artist who Cannot Speak English is no Artist.” When I

lived in Italy I remember that neo conceptual artists from Northern Italian

cities outside Milan would come to Milanese openings and loiter outside (never

entering the gallery) in a symbolic gesture of how they were excluded from

mainstream exposure. Similarly, the Eastern European Stilinovi seems to refer

to American cultural hegemony. Like some Dantean torture in Hades, non-English-speaking

artist view the laurel crowns of their peers at a distance. Or perhaps

Stilinovi questions the legitimacy of “internationalism,” wishing to

conserve regional culture at all cost. Linguistic barriers once again obscure

the meaning to an American viewer. Dalibor Martinis exhibits an installation of

eight sheet music stands that are arranged following the semicircular contour

of a wall. The stands are placed eighteen inches from the wall and between them

are odd numbers of potted corn plants. There is no sheet music on the stands.

What seems outwardly to be an Arte povera statement about material, in the

context of Eastern Europe takes on darker meaning. Poverty, opportunism, ethnic

rivalries, and war seem to alienate higher forms of cultural expression.

Invisible musicians play against a wall with invisible music, or do they?

Chinese Whispers, curated by Branka Stipancic and Ana Devic from October 11 through November 11 at Apex Art Curatorial Program, 291 Church Street, New York, New York 10013, telephone (212) 431-5270.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2000.