Alanna Heiss on Sound, Space, and the City

DKR – Having won a scholarship to the Lawrence Conservatory, your first creative venue was music. What do you see as the distinctive potential for sound to convey narratives and experiences in art?

AH – I come from a family of musicians. My uncle was a composer who eventually became the Head of Composition at Julliard here in New York. He was one of two people who ran a fantastic program at Iowa which brought out everybody from Robert Wilson to John Cage. My uncle was a traditional composer. His daughters, who all went to good conservatories, were trained as violists and violinists. That was also true of my other cousins. In fact, almost all of my cousins and their children have made their living by playing stringed instruments. I was the person who was least good. I played violin, harpsichord, and piano. I trained in piano for twenty years, but I wasn’t what anybody would consider a good solo instrumentalist, though I probably thought I was, because I came from a very small rural town, Jacksonville, not so terribly far from Saint Louis. We had a lot of traffic between Saint Louis and Chicago, which was one of the arteries used by black folks who were coming up from the south and headed towards work in Chicago. I attended school in Jacksonville, where we had a sizable population of black parents and their children. The town was not segregated, thank God. Most of my musical experiences were formed by the classical lessons I took, and by practicing a requisite number of hours a day. But they were also shaped by my experiences with the children I grew up with, who performed post-spiritual, early pop music compositions. They were doing four-part harmonies, blues was starting to go into rock and roll, and the feeling was if these kids could get any recognition, they could get out of the desperately poor situation they were in. So, I learned at that time to record and write music as it was sung to me. This kind of training was invaluable for learning how to listen, and especially how to listen without elitist concerns, and how to listen in order to help another musician. These were all non-performance experiences which were very important. The last thing that I learned, before the conservatory, was to be an accompanist. I made a little money from this, and though my parents were schoolteachers and we weren’t broke, money was always very welcome. So, I accompanied church choirs, sometimes two or three times a week. That meant I had to learn how to play rudimentary organ, which I could do, and I needed to be able to watch directors, accompany the choir, and try to see and understand the relationship between a large group of people trying to collaborate on a single action.

Learning how to accompany was one of the most valuable things I learned in order to work in the art world and in museums. I would accompany single artists, other people who were destined to become concert artists, and also choruses. It’s watching the artist for the sign of the cue, about what they want to do, and which they will communicate to you non-verbally, that makes you a good accompanist. It’s that very skill which has made me very good at working with artists, because I watch them all the time.

It became very apparent during my first year that I wasn’t going to ever perform in solo concert violin. My teacher suggested that if I continued to do this I would be disappointed. I asked, “What would be my future” and he said, “You could be second violin, second chair, in a third-rate symphony.” I said, “Oh my God! That’s terrible! Where would that town be?” (because I’d never been anywhere but Jacksonville, Illinois or Appleton, Wisconsin). He said, “Well probably somewhere in Nova Scotia”, and although I’ve since learned to respect Nova Scotia as a site of orchestral music, at the time it seemed a very unpleasant place to be because it was so much colder than Wisconsin. Although I did get my degree in music, I also got a degree in other artistic and cultural areas, which broadened my experience greatly over those of my conservatory friends, who often had to concentrate on one thing and do it over and over again.

You asked me about conveying narratives and experiences in art. This classical endeavor I learned through Max Neuhaus. Max and I met at the Clocktower Gallery, where you and I are sitting now. He came in to talk to me because he knew I had a musical background and he wanted to know if I could advise him about sound installation. Max and I were together as a couple for maybe four years. Max was a really unusual man, and I don’t speak lightly. I’ve worked with a lot of unusual people and a lot of unusual performers, and I’ve been the manager of rock bands and traveled around the world. But he was very eccentric. Max, who was quite shy and didn’t want to be in a room with a lot of people, was able to convey to me attitudes and issues that I had never encountered before. One, which I quickly adopted to be my own, was his observation that the music world – and he’d been a protégé and performer at Carnegie Hall and had traveled around the world as a percussionist – only wanted people to play repetitions of works that had probably been written more than two hundred years ago, or at least one hundred years ago. It was impossible to compare this with the art world because they were not the same generic items. Artists and the art community of New York City wouldn’t be interested in painters who were able to duplicate in a craft-like sense a painting which had been made a hundred-and-fifty years ago: that wouldn’t be considered a very interesting way to extend the narrative of new art. By that very simple comparison, I began to realize the great gulf between classical music and contemporary fine art. I essentially dropped classical music as something that I remained involved with – its narrative really had never been of great interest to me – and I became involved with the outlaws of classical music who, at that time, were Phil Glass and Steve Reich.

My feet are now so firmly planted in the contemporary art world, and this has been the joy and vision my whole life – I’m happy that I made this choice. When I hear a concert, and of course I still listen to classical music from time to time, I see these performers as almost robotic. Because of Max’s introduction to me of the variety of extraordinarily exciting abstract areas of sound and music, I jumped over to that. From 1974 on, I’ve been involved with the great composer and protégé Elliot Sharp. Of course, we all knew La Monte Young because he was a visual artist posing as a blues band person, which he enjoyed as everybody does. And Max also taught me about Stockhausen and the whole scene that erupted in Europe, and that led me to understand more about the Wagner I had studied as a child but never understood.

At the same time, I rejected classical music as a formative structure for belief in all things good, I also reverted to my early days of rock and roll and working with popular musicians. That was not anything Max was remotely interested in and he wasn’t patient with it, so I carried this out by myself. As soon as Max and I were going down different roads, I started spending a lot of time with bands, punk bands particularly. Joey Ramone was a close friend and I used to go to all those performances. I was a single mother who wanted to go hear a lot of bands and my child was very young. At first, I started taking him, but he was such a baby. Robert Mapplethorpe, who was a very kind man, and a very careful person, encountered me I think at a bar, perhaps CBGB’s or The Mars Bar or Mercury Lounge, and said, “You know a baby shouldn’t be here, there’s too much smoke and there’s too much noise.” I said, “I just can’t afford baby sitters.” This was in the early seventies. He said, “You’re right, you can drop the baby off at my studio because I have studio assistants that work quite late, and I never go out until 3:00 am so it’s no problem for me.” So that’s exactly what I did – about twice a month I would drop my son off at Mapplethorpe’s studio, and these extraordinarily kind and careful studio assistants at the studio would take care of this bundle of joy who would sleep through it until my return. So, my experience of New York and the music that was going on was actually quite unusual. The Kitchen was running substantially important programs through Rhys Chatham – they really had the right curators at the time for music. And I had my own peculiar connections with Debbie Harry and other English musicians because I lived in England for four years. Everybody knew who the Stones were, but I actually knew one of the Stones or knew a Stonish person.

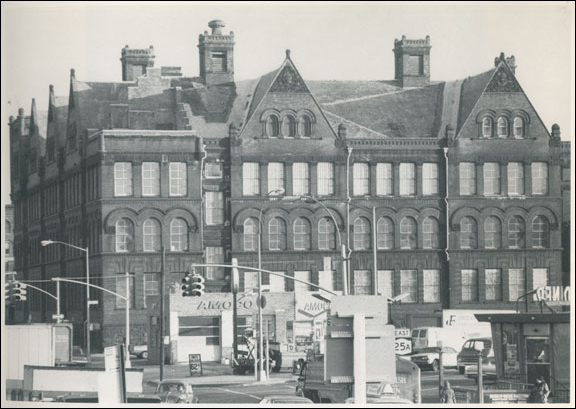

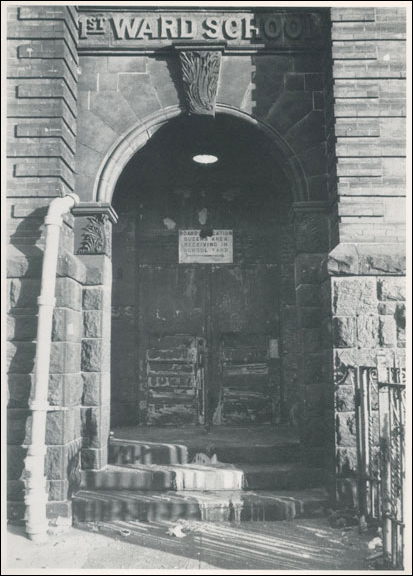

Bringing all this together was something that was very much a part of the way I looked at life in New York City. I’m an outsider, I come from a small town and I’m full of wonder that all these people come to New York and do what they do. The wonder has not gotten any less even though I’ve lived here and I’m now sixty-eight years old. I’m still just astonished by the talent that has accumulated here. With that humble sense of wonder I’d like to do everything I can to make those worlds come together, and P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center was one such place. In the eighties we had a tremendous amount of what I guess would be called “traffic.” We had a lot of traffic with people who I asked to be curators, and who were often club organizers supporting themselves to do other things, like art or dance. I would ask these people to involve themselves and their thought process visualizations in studios at P.S.1. This was very much an eighties thing which made P.S.1 a center for people from all different kinds of arts. P.S.1 itself was like a velvet rope museum. Only the “in” people knew where it was. We had never put even one advertisement except once a year in The Village Voice we would put a full-page ad saying, “It’s an opening.” There were no published hours and many times people would come and they wouldn’t be able to get in. I closed it at random, always during the summer because everybody was running around doing something else, and there was no institutional methodology in the eighties. We started to change because P.S.1 became immensely important as a venue. It became a very powerful assignation for artists and institutions to have.

I then started asking real curators to work there and having real programs. But one of the terrible things that happened was the effect AIDS had on New York City’s nightlife. P.S.1 was like a night museum (we were always there until ten or eleven at night), and it was this strange gothic headquarters. Europeans were there and everybody was there – painters, sculptors, filmmakers, dancers. After P.S.1 would close, if it ever did close, we all went to the city and then to clubs. The club world and the art world were absolutely connected, and the club world and the musician world were very connected. This is before the DJs controlled clubs. When AIDS came, it supplanted every concern of every other kind. The only important thing was staying alive, and staying alive not in a marvelous anthem sung by a great female vocalist, but staying alive as keeping oneself from becoming one of the increasingly ravaged ghosts who were walking the streets. Everybody immediately put away concerns that had to do with music and sound and dancing and nightclubs and rock and roll. They turned to the visual arts as a more pure form of narrative, that was not temporal but something that would last.

My concerns changed, and although we were never a collecting institution, works did change toward presentations that could last in the sense that they could go into someone’s home. They could be a record of this or that. It’s my observation, and I don’t know if I’m right or wrong, but oddly the concerns in music turned back to more somber, elegiac, mass-like forms. Nobody felt like laughing. It seemed that people stopped dancing in New York City. I know this is something everyone my age brings up because we lived through it. But in addition to its global importance, in that it just killed thousands of the most important artists around the world, it completely changed the way in which those of us who showed art and those of us who made art in this city directed our energies. New York shifted – there was no longer any way to behave like we did in the early eighties.

DKR – Would you speak about your pirate radio experiences with Radio Caroline and nationalist guerilla radio in the hills of El Salvador?

AH – I was living in London during the time that Radio Caroline became a beacon, not a virtual beacon but an absolute beacon, a real beacon / sound vehicle for untrammeled popular music. Since I left classical music, my interest was almost zilch with the possible exception of Max Neuhaus’ work. I was fascinated by this idea that, because you’re offshore, you could program your own radio without being tethered to the concerns of either the BBC in this case or in America the concerns of the, now we largely learned, B rut radio broadcast system. It became possible for me one time to go out on a boat with people who were dropping off a DJ or composer at Radio Caroline. I got to spend the night running around the boat and looking at everything. In no way was I a part of running Radio Caroline, but I certainly got to see it and see how the people were running it, and how much fun such a situation could be. Though not on a boat, I vowed I would have a radio station in my life. Radio Caroline was much more than a radio station, it was a symbol of the feeling at the time that breakaways were possible and that we represented, as an age group, an alternative form of government and belief. Obviously, it was just a silly, huge bad boat with average DJs on it and everyone was drunk and drugged all the time so the programs were very low quality. But the idea was that you could have a capital of this imaginary fantasy world that all of us were members of. Some groups printed passports and one group, twenty years later, called – NSK – Neue Slowenische Kunst – were growing up and into the revolution at that time, and were imitating a government function in every area. They had five departments – one was philosophy, of which Slavoj Žižek was the director, one was dance, one was theater and one was music, which the great band Laibach came out of. They had these parallel agencies to paralyze the Soviets and the administration. Because it was a tiny country and these artists were extremely charismatic, convincing, and powerful, two things are worth mentioning. One is that they were able to have passports printed by the same printers making the actual passports for the government. All of us got NSK passports with our names on them, and they worked in many countries. They not only looked official – they were official. You could call a number and a person would answer for NSK passports. I mention this because it was a twenty-year later scheme that NSK came up with, and I’ve talked with many of the members about this, that was inspired by many of the quasi-governmental wild-eyed situations like Radio Caroline. NSK’s identity was the opposite of loose, crazy and drugged. They were involved in absolute irony, and we were certainly not.

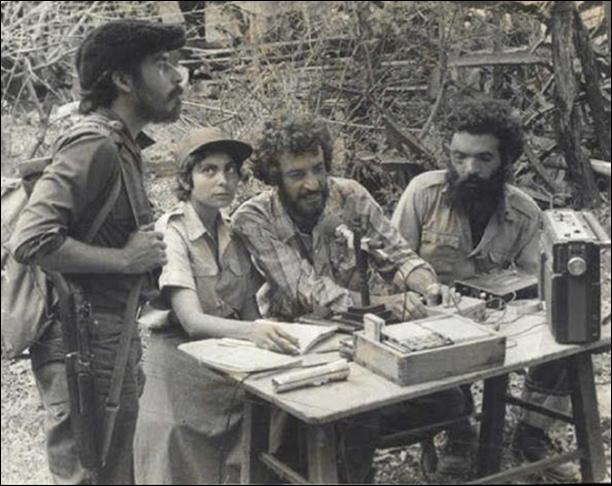

You asked me about El Salvador so this is a new story with an old story. The new story about El Salvador is that I was invited to be on a jury for a biennial happening in the Caribbean, and I was very attracted to the idea of the title. I had an incredible vision of these five days spent in a luxurious resort and meeting very relaxed and pleasant artists who didn’t really have careers but who were sort of Caribbeanish. So, I accepted the invitation with alacrity. I was sent the ticket, packed flower shirts like I have on today, jumped on the plane and started sleeping. After two hours I started thinking that this was kind of a long way, and I wondered which island we were going to. Then after three hours I thought “this is a longer flight than for any island.” Max Neuhaus had a boat in the Bahamas, and I spent a lot of time in the Bahamas on that boat with him. He was doing underwater sound recording, and that’s where he lived, and I was just having a good time. So at our number four I asked the stewardess where this Caribbean island was and she said, “It’s not a Caribbean island, we’re going to Central America, we’re going to El Salvador.” I said, “Oh my God!” Now this was really quite different from what I anticipated and what made it even more serious was that I had nominated two artists for this project, who had agreed and were already there. So, I arrived in El Salvador with a great deal of foreboding – it wasn’t a Caribbean wonderland, it was a country that was a huge parking lot. We’d bombed it to smithereens and covered it over with cement. It was a very anti-American underneath, pro-American on top situation, and I had such distinct memories of our involvement with the CIA in El Salvador that I was extraordinarily apologetic as I was coming down the steps of the airplane. How could I make up for this in my own way with the artists? What happened which was of any interest to this story was that I was moping around the strange, boring, dull Holiday Inn, looking at people at the bar, looking at the work in the biennial which was not in any way unusual or unconventional, just normal art, and I finally wondered how I could make contact with some of the people who had been involved in the revolution as administrators. My thinking is always administrative because that’s what I am. I was talking to some of the artist guides and they said, “It’s very hard because there are not very many roads, but we can take you on a trip to meet some of the retired guerillas and talk with them.” I thought this could make a good radio interview so it took some money and some arrangements, it wasn’t dangerous or anything, it was just inconvenient. So, I went off and took a couple of colleagues who I had nominated for the biennial. We all got into this gigantic Hummer with an underground guide and so-called guard and went into the mountains to meet the guerillas. They’d made appointments for me based on the fact that I ran a radio station out of P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center called WPS1, and we went through four hours of incredible driving – crawling up ravines to see the first retired guerilla. I found out what was mind boggling and has very much affected the programs here at the Clocktower, is that radio is the single most important thing to the guerilla movement in any country. Radio’s cheap, you can make a radio – fourteen-year-old boys are the best people to make radios – and you don’t need to have roads, so in all these places with difficult access, where guerillas are in pockets all over hiding, communication is by radio. The second thing is that those with the most power can always control the television media. They control the stations and those waves are never used by radicals because they don’t have the equipment. But not so with radio.

The guerillas who had retired and made deals with our government were living not in splendor but in a certain comfort. In one camp I visited they had no television – they would have liked to have television, but didn’t. They had a bunch of broken-down horses, very beautiful wives who were cooking fantastic food, and we sat around and through translators talked about radio and how they had run their revolution with radio. Two of them had decided they wanted to start radio museums – so my next visit was to this guerilla with a radio museum. I was fantasizing about what this radio museum would look like. Mainly I had this idea about a futurist spaceship that had been built with a big antenna on the top. It was in a town of about nine or ten people, very dusty tiny little town, with no street life, because everyone was very afraid. These villages are quite dangerous because of drug runners. The radio museum was on a second floor above a bodega and had a hand-lettered sign saying “Radio Museum” with an arrow pointing up. I went up the stairs, and I encountered what you could encounter in the Clocktower right now. The studio is very, very messy. The studio of every radio in the world is very messy. They have illegal cigarettes because you’re not supposed to smoke in radio studios and they have some sort of liquor in paper containers in which they put the cigarettes out. I’ve been in radio studios in throughout Russia, China, France, everywhere – I lived in a radio studio the summer before last and we were doing recordings for six months. They’re always the same. Then there are some dirty clothes around, there are always some dirty socks, and always some clean laundry so they can go out. In fact, radio is timeless, so people who work in radio are never paid anything and they more or less live there, and they don’t know what time of day it is, because it doesn’t make any difference what time it is in radio time. There’s no time in radio time. The guerilla with the radio museum was wonderful and he said, “If you want to move here, you could be our producer.” I think of it a lot. Not speaking Spanish is a drawback.

DKR – What was the initial impetus for your founding WPS1?

AH – It was the romantic desire to have a radio station. Because P.S.1 was very isolated in Queens, and we had the advantage of being able to go under the radar very easily, I thought I could put an antenna up. But I quickly found out that if you have an antenna, you are discovered immediately. Wanting to keep my non-profit status, though I wouldn’t have lost that, I had to keep on the right side of the law and radio stations are extremely self-protective. So, the only thing you can do with a radio station is to invite all the new people in as fast as possible and get them on the air, which is what we do here. So, after the antenna thing was shot down, I then tried a low-signal radio in a van that we would drive around the area so we couldn’t be caught because it wouldn’t be from any single place. We would park, do some programs and then go somewhere else, park and do programs. We did that for a couple of years just off and on. For me it created a delusion of being an outlaw. It wasn’t in reality at all effective, it was just fun. Most of the things that I do are fun for me or I just wouldn’t do them. Starting in 2000, I fundraised to make the project more substantial, and I turned to the Clocktower, which I’d kept as an alternate to P.S.1. P.S.1 was an alternate museum, and the Clocktower was an alternate artist’s space, and we made the Clocktower the broadcast station. When I left P.S.1, I freed WPS1 and its audio archives, and restarted it as its own station at the Clocktower, and now we have the gallery and the radio all together

DKR – How do you see the rapport between visual art installations in the Clocktower Gallery and your radio programming?

AH – Before I came to work full time I made it a pretty clear connection, but working here, what we really have is a kind of artistic colony of anywhere between five and fifteen artists doing projects. Radio is an extension of the ability of the artist to communicate to a large group of people without having them physically present. At P.S.1, until MASS MoCA, I had the largest space in the world for contemporary art of a non-collecting institution. It’s the same size as the Prado, different as the interior may be. But here at the Clocktower is a thirteenth floor which is a sinister, macabre, gloomy, rooms-thrown-together, but beautiful place, and we have artists inhabiting these rooms, and anything that happens here in a visual art capacity can be, if needed or wished by the artist, promoted through the radio to a vastly expanded audience. The shows I do tend to be more like laboratory shows and be up for a number of months. They have a certain archival nature. James Franco, for example, produced a series of radio programs that had to do with his films and sound for his films. Our archive is so huge, it’s like a collection. So, for the first time in my life, the most radical activity, which is a radio station here, became also a collecting institution which I never was involved with. I think that’s interesting.

DKR – How do you think social media and internet radio are transforming contemporary art?

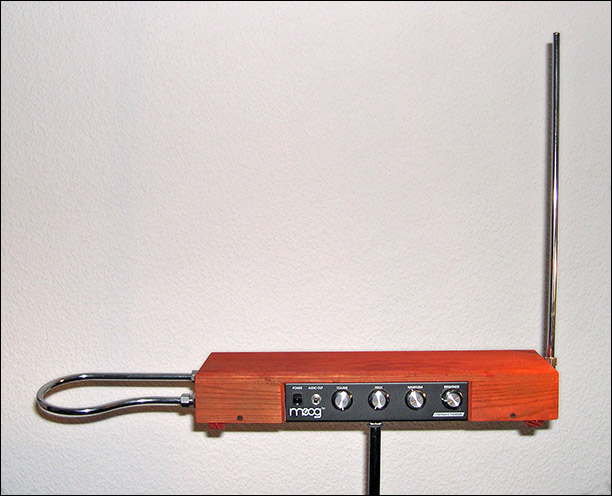

AH – Social media and the internet are certainly transforming contemporary art – they’re transforming everything. I’ve never learned how to use computers. One of my problems was that I couldn’t and can’t type. I took typing in high school but I cut class all the time. In the summer I went fishing instead of typing and in the winter, I took tap dancing instead of typing. So, I would hide from computer-related activity, and I wrote everything on legal paper. When faxes came in, I was a fax queen because I hand-wrote, and Harald Szeemann (the greatest curator who ever lived) and I always communicated by fax. He had the same problem I had. To actively work with our radio station, however, I had to learn something, so I’ve adjusted to iPads. Now that online radio makes use of look-like-a-radio-instrument computer software, I’ve overcome all these problems, but before, I did everything in my imagination because I didn’t know how to work the internet. As an outsider to the internet, I can tell that it has changed everything. It’s impossible for insiders, who have grown up with the internet, to understand that. Visual art tries to claim that it is excluded from this mass ultimatum, but it isn’t, because I look at the invitations now to shows on my iPad and I have a different relationship to the invitations and the pictures of the work. Backlighting and the luminosity have become very important to art because you’re always looking at it on a computer. Even the most pedestrian designer can either make a beautiful invitation card for an artist and make everybody want to go to the exhibition, or completely kill the work so artists have to learn to do their own graphic design or they can’t survive. All visual information is transferred by the internet. There are no slides anymore. I’ve traveled the world for forty years with slides. It’s so ludicrous to even think of conveying information by slides anymore, that people talk about Robert Smithson’s slideshow (which is by the way owned by the Whitney) as an art piece. The kids at the radio here say things like, “wouldn’t it be wonderful to go and see the beautiful Robert Smithson slide piece?” This is ludicrous! He had the slides like I did and other people did, just of some geographical conditions and it was always a good slide show but it wasn’t a Slide Show. Slide shows now are Theremins.

DKR – What’s a Theremin?

AH – Theremins are instruments that were popular for just a few years in the forties and fifties. It’s a keyboard with electronic waves coming out of it, and you play it by breaking the sound waves and waving your hands around. It would be familiar to you only if you’d seen old science fiction television programs in the sixties. Speaking of Theremins, my colleague David Weinstein, the Program Director at the Clocktower, is a Theremin addict so he’s very interested in it, and when we did a big project in Venice this past summer we had a Theremin player, Massimo Simonini, every night in a sound lounge we did off the Piazza San Marco. Of course, there were crowds of people because no one had ever seen one before and they’re very antique instruments.

Will art as a visual object just become unimportant? Who knows? In many cases the need has become more desperate to have something that is not flipped away immediately so people are clinging to art objects. Our youngest curator, Joe Ahearn – in fact only curator but I like to say youngest because Beatrice Johnson and I are sort of curatorial tycoons here – is twenty-five years old and a very important young artistic talent. He is involved with all the music houses which are in Brooklyn and was one of the key members of Silent Barn. Silent Barn is a great bad place to go and there’s music all the time, people live there, there are bands there and Joe is instrumental to it. Unbelievably, Joe and his friends produce a newspaper on newsprint every two weeks and it has no use whatsoever because as internet children, which is what they are, they know that all this information could very easily be conveyed on by the web – but no. They list every single band, every single time, every single alternative music place, even bars, in the whole area of New York, Brooklyn, the Bronx and parts of New Jersey. They assemble all this information together, and probably do that from the internet, and then they typeset it, design it, and then they have artwork made for every issue, and they print it. It’s called Showpaper and they print it in Long Island City, and then twenty or thirty of these young artists get together in a distribution system and distribute it throughout this gigantic area by hand. Artists of their ilk and age have built newspaper stands, which are so tasty that they’re constantly stolen, but they keep building them and you can go to the stand and get the paper and the reason for all this effort is to have something you can touch about something you can hear. Isn’t that phenomenal?

DKR – So it’s about community too and the physicality of a connection you make with another person beyond the ether?

AH – They’re internet children so they’re rejecting this method of communication. I think it’s the most interesting thing that we could talk about today. Your magazine is not going to be printed. A person deciding to start a magazine today like ARTERY who was determined it would only be in print, would have to be a mad person. Maybe not mad but odd or very eccentric.

DKR – But the fetishism of a beautifully printed magazine on paper as an object you can interact with in that way is very different and appealing.

AH – I think you’ve really hit the right word and even Joe Ahearn has agreed that what they’re doing is fetishistic even if it’s really innocent. It’s innocent of time and innocent of money. I’m very curatorial and love the thing they’re doing so much, so I wondered how I could make it mine with this great idea and great effort. I can’t even cover the printing costs because I don’t have any money but also it’s unviable, and they won’t print an ad. We’re very friendly with the Brooklyn Rail and Phong Bui is a close, close friend of mine. The Brooklyn Rail and radio have always been together and everything. Phong gives us the only ads we’ve ever had. He says it’s an act of rebellion these kids are doing, and The Rail is very close to that. It’s old-fashioned, they hand it out, it’s all-volunteer, only one person is paid, so they’re very, very close but they’re not as crazy as Showpaper. Showpaper has the craziest people around, the next craziest of course are at The Rail and the third craziest would be us here at the Clocktower Gallery and ARTonAIR.org.

DKR – Do you believe that our post-9/11 world and current economic downturn favor more experimental approaches to artmaking?

AH – I think two things are true in the last ten years. The collapse of the lingering idea that the US is invincible made people decide that they wanted to put their money into something very tactile and real. This meant that a lot of collecting went up right away after 9/11. The rich not only got richer, but they made many artists rich, and the economic upturn of the art world was phenomenal not just because of September 1, but because, in general, people were more interested in the global reality of art than they were in anything else that was going on because in a puff of smoke it could disappear whereas art, my goodness, that could last years. So, a lot of artists got very rich in the last fifteen years, and they’re even richer now and there was little experimental work being made because it was the first time you could actually go into art as a career. People are proud to say that their children are artists now because they’re going to make a much better living than anyone but an investment banker. However, at the same time, there emerged a true underground for the first time that I’ve seen since the seventies. What the technical world has given young artists of this time is a cheap way to actually deliver things without manufacturing or having to run expensive galleries, so most young artists are exploring their own kinds of virtual galleries and virtual realities. Unfortunately, the fly in the ointment is that you have to have a good IT person to do it. So, it’s back again to the experts, no longer the people like me who are the curators, the accompanists, who are trained to run museums and do these things. Now you need people who have graduated with a degree in computer science and you hope that they are radical enough that they want to help bring your ideas to fruition.

DKR – Do you feel as though you’ve come full circle in pushing virtual boundaries of sound and new media today like you changed people’s vision of what an exhibition could be in the seventies?

AH – The question is a happy one because for me there’s a happy answer. I don’t know when I’ve been happier! Although I would have liked to stay at P.S.1 another year, just because there were some specific shows that I was involved with and wanted them to materialize there, I was always anticipating future life at P.S.1 without me. So, the actual exit for me was not a problem but the timing of the exit was because I had to cancel several big shows. Having left P.S.1, I had the opportunity to do any one of a number of things and I really looked at a lot of them and thought about coming back to the Clocktower, because it was a circle, and it was kind of funny to do all this and come back to exactly my same office. So, perversely and ironically, I set up my office in the same place with the same stuff. Of course it’s dressed up, and the bookcases have books on them, they don’t have only technical equipment. The technical equipment is in the radio sound system. All the rooms I had worked with in the eighties – the Clocktower was around, it just wasn’t very prominent. Being back here and close to very young people has been so exciting. P.S.1 was wonderful, but it was so huge and I got very engaged with meetings happening all over the world, and I stopped seeing as many artists as I used to see. In the beginning, the building’s size helped me see more artists, but by the end of my tenure at P.S.1, I was more separated from artists because of it. I could just run in and run around the whole place and put a lot of shows up and then run away again and go to Istanbul where all my friends are now, as we talk, they’re all in Istanbul, but I’m here and I don’t mind being here because what’s happening here is so much fun. It sounds like a person who’s on Zoloft, which I’m not, but we’re trying new things. Last year I was completely involved in taking chances on something that had a lot of potential – Radio Theater. I wanted to try to integrate some of the actors who are all here in New York (I didn’t know about them until radio) with some of the interesting writing going on, and do radio theater. We started out with a couple of very good projects, but they didn’t develop to be as weird as I thought. It was more like readings. By the way, there are only five people here working, so you can’t run a whole theater company.

One of the projects we did was by a director, Peter McCabe, who was writing a piece about Stanford White and his death, and since he was the man who designed the Clocktower with McKim and Mead, it’s very funny to view The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing around here. That was interesting and fun and it was theater. And actors don’t care what space they’re in because they’re always in rehearsal spaces. They’re not like visual artists and collectors. I learned a lot about actors last year. We would put an ad in for no money (by ad I mean a notice up to be in a play for no money) and we would have dozens of people here getting through the court security people downstairs. They’d just get right through it – they’re actors! Right? They’d get to the thirteenth floor, they’d come down here to this room and wait and rehearse and audition and leave and they would not even notice that anything was odd. I think that’s pretty odd!

The most exciting thing that I’m looking at is the presence of live bands. I’ve noticed that when we had bands, real live rock and roll bands here on occasion (which we’ve had because they’re doing performances here at the Clocktower), the interaction of a rock and roll band in the middle of a fine art operation like this is extremely healthy. I think this is because of the anti-intellectualization that the band represents. They represent a kind of gross stupidity that’s adopted, even if it’s not real and is a kind of position and style, “We’re a rock and roll band.” Meanwhile, deep in their hearts, of course, and I know this from spending forty years with rock bands and friends, they want to be seen as artists. Scratch a rocker, find an artist. So, what we’re starting is a studio which will have the facilities and ability to be a recording studio, and we will invite a band to be here when they’re not on tour, and they can rehearse and play for a couple of weeks. It will be very destructive of course to everybody else because it’s a lot of noise. This has already been seen from experiments we’ve done – including bands such as Japanther and a small punk rock band, the So So Glos. It’s just humbling what happens. You can’t hear anything and they’re always wandering up and down the halls and opening doors, saying, “Hey! Who’s there now? It’s a break time for us!” It’s a completely different way of working. So, I want to do this over the course of a year. I want to have nine different bands come in and we may go as far, perhaps, as a Jazz percussion band.

I originally wanted Justin Lowe and his collaborator Jonah Freeman to do it, who make all those extraordinary environments that I’m sure you’ve seen, the strange meth complexes. They did a big show at Jeffrey Deitch’s before he left a couple years ago that was phenomenal. Justin, who’ an artist I like to work with, was going to do a recreation of Lee Scratch Perry’s studio at the Clocktower. Lee Scratch Perry, who is alive and lives in Switzerland, is supported by a wonderful woman who married him and who believes in aliens in outer space, and believes that he is an alien. That’s very convenient because Lee Scratch Perry is out of his mind. He would have been killed or in an institution if he wasn’t in Switzerland living the life of the truly insane. He’s a Jamaican who recorded in his crazy studio all of the important Jamaican music in Kingston and did it with analog equipment. When he started truly going mad, he started writing on the walls of the studio and writing more and it became this very intense, very deep collaged place, and by that time all musicians would go down to do this, even the Stones. They wanted to see it because it was a famous studio. They would flip out when they’d see the written material visualization that Lee Scratch Perry had engaged himself in doing in the recording studio.

Then, in an act of insanity, he burned down the studio, nearly killing a number of people who were in the studio and were his sound recording people and then he went into his house and sat. He would be resurrected and taken on tour to various places. He was in New York supposedly a few months ago, but I don’t think he turned up. He usually doesn’t turn up because he can’t get through customs anywhere. The last time I saw him three years ago, and I think this is something he does a lot, he was covered with a cape made entirely of small mirrors strung together and he has the Rasta hair. So, we thought we’d recreate the Lee Scratch Perry studio here. We thought that would be an ode to him. It wouldn’t entirely be a reproduction, but it would give sort of the right vibe to the space. It just turned out to be insanely expensive to get this analog equipment! I spent all last year going around asking recording studio people and rockers if they would donate their analog equipment and initially they would say, “Oh yes, you can have everything you want!” and then when we got down to picking it up they’d say, “Oh no, we’ve decided…” because they found out that there’s this fetishization of sound now that has to do with analog equipment. We were going to use analog because we couldn’t have anything else. We couldn’t imagine getting the equipment, but by the end of the project, which didn’t happen among other reasons because we didn’t receive an expected grant, we would have had non-working analog equipment and would have had to fake with the real digital equipment hidden. That was no problem for our project because it was an art project, not a sound project, but now we’re just back down to rock studios. We may have to move our offices or something, but you’ve got to stop thinking and start listening. Max Neuhaus named his not-for-profit organization EAR and he was always fooling around with H/EAR. One of his first conceptual pieces was called Listen. He would take people on long tours and they would have to listen to everything, and because he came out of the percussion world of the sixties, it was important to hear. He liked very soft tiny sounds, and of course I love bass. Anyway, listen and learn!

Special thanks to Francine Hunter McGivern.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2011.