Gillo Pontecorvo and the Cinema of Revolution

Irene Bignardi’s biography Memorie estorte a uno smemorato (Memories Extorted from a Forgetful Man: The Life of Gillo Pontecorvo) was published in Italian by Feltrinelli in February of this year. It is a fascinating document that traces his career from early years as an aspiring tennis player to his role as a liaison between the Italian and French resistance to his brilliant efforts as a film maker. It is a highly personal look at the man whose political activism, acute ear for music, and sense of editing form led him to produce such compelling films as Kapò and The Battle of Algiers.

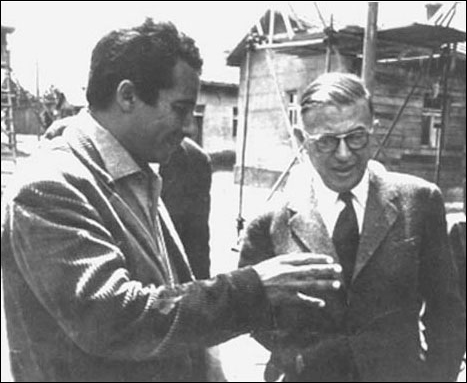

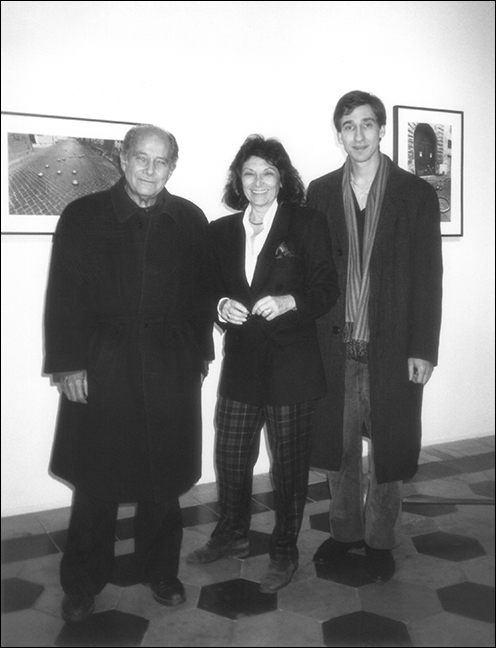

I first met Gillo Pontecorvo in 1994 in Rome during his five-year tenure as director of the Venice Film Festival. The critical faculties and perfectionism that limited Pontecorvo’s production as a film maker served the festival well. He wished to ameliorate the condition of cinema, a “sick” art form afflicted by the ailment of banal commercialism (most rampant on this side of the Atlantic). He has a youthful presence despite his seventy-nine years and striking, limpid blue eyes. On speaking with him I soon came to appreciate the breadth of his life experience and diversity of his talents. Bignardi’s biography discusses these interests at length and how, at times, they dovetailed with his work as a film-maker.

Pontecorvo first attained prominence in this country for having directed the Italian/ French co-production Kapò, which earned him the 1960 Academy Award nomination for best foreign film. Pontecorvo and Franco Solinas had decided to make a film that addressed the concentration camp experience of World War II, and researched the project by interviewing survivors throughout Europe. Ultimately, they took inspiration from the writings of Primo Levi, whose Auschwitz memoir If This Is A Man evokes the surreal horror of these camps where prisoners were methodically stripped of their human dignity.

Kapò tells the story of Edith, a fourteen-year-old Parisian girl who is deported to Auschwitz with her parents. Her parents are sent to the gas chambers upon their arrival, but Edith has the good fortune to meet a physician who exchanges her identity papers with those of a French criminal who had died the previous night. As a result, Edith is shipped out of Auschwitz with a detail of women to a small forced labor camp. Gradually she becomes hardened by camp life, loses her sense of empathy for other prisoners, and becomes the mistress of an SS Officer. At last she submits to the ultimate degradation of becoming a “kapo” or Nazi administrator of fellow prisoners. Edith’s humanity is rekindled by her affection for a Russian prisoner of war, and ultimately, she sacrifices her own life in order to help others to escape.

Pontecorvo develops a complex reality in which prisoners occasionally rise above their struggle for survival for the common good. Pontecorvo sought to obtain a newsreel, documentary effect, and toward this end he printed film from his negative and then re-photographed it to obtain a print that had different, rougher qualities. Pontecorvo also employed a number of non-professional actors on the set. He selected them for the expressive qualities of their faces and coached them with a highly convincing result that is reminiscent of the work of Sergei Eisenstein. Pontecorvo also made highly effective use of the score by Carlo Rustichelli as well as incidental music. One particularly moving scene involves a group of Russian prisoners of war who sing The Sacred War in chorus. The Sacred War is a nationalistic hymm that was broadcast each morning on Radio Moscow during the war, and when sung by these bedraggled soldiers, it defines their powerful spirit of resistance.

A theme that carried over from Pontecorvo’s direct experience during the war to his work as a film maker is the struggle against oppression in its broadest terms. As Italian Jews, his parents had a number of close scrapes with the Nazis, and Pontecorvo fought in the Italian resistance. In a discussion with the author, Pontecorvo declared that Kapò is his favorite film due to the quality and intensity of emotion that it elicits. Although Pontecorvo did not have a camp experience himself, the film raises great questions about the nature of sacrifice and purification through suffering. Kapò was made by a man who had made difficult decisions concerning life and death during wartime, and the result is a passionate, moving film.

Pontecorvo’s next film, The Battle of Algiers, is considered by many to be his masterpiece. In 1964 he was approached by Salah Baazi, who sought to realize a film about the struggle of the Algerian people against the French colonial presence. The Algerians were considering Francesco Rosi, Luchino Visconti, and Gillo Pontecorvo for the job, but Rosi was at work on another project and Baazi failed to reach an agreement with Visconti, so the film came to Pontecorvo. Pontecorvo and Franco Solinas had already explored the possibility of a film about the Algerian conflict two years earlier that would have interpreted the experience of a right-wing French photographer in Algiers during the rebellion. The Algerians, however, wanted a film that told their story with Algerian protagonists, so Pontecorvo and Solinas set to work on on a new screenplay.

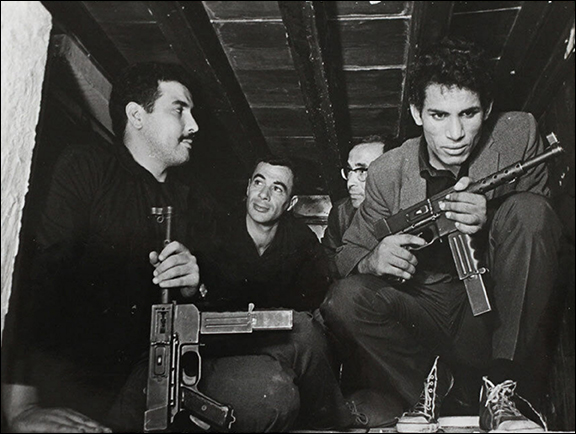

The Battle of Algiers examines the struggle of FLN guerrillas against the French army as seen through the eyes of a young revolutionary known as Ali La Pointe. At the beginning of the film Ali La Pointe is depicted as a small-time con artist, lacking direction or any political consciousness. Ali La Pointe is thrown into prison for striking a pied noir Frenchman, and from the inside he witnesses the execution of an FLN revolutionary. As the condemned man is dragged toward the guillotine, he chants “long live Algeria!” and the other prisoners join in. After his term in prison, Ali La Pointe is contacted by members of the FLN and enlisted in their cause. Ali La Pointe begins to implement military strikes against the French authorities, and as a result of these incidents, the FLN calls international attention to the issue of Algerian independence.

The French, in turn, send a special parachute division to Algiers under the directon of Colonel Mathieu, a man who is experienced in counter-insurgency methods. On the eve of a United Nations vote on the Algerian question, the FLN calls a general strike in which most Arab merchants of the casbah participate. Colonel Mathieu rounds up many “suspects” among them and through torture, succeeds in reconstructing the network of cells in the FLN command. Overwhelmed by superior forces, the FLN gradually disintegrates until only Ali La Pointe and a handful of others remain. Ali La Pointe is ambushed in a hiding place in the casbah, and upon refusing to surrender, he is murdered with plastic explosives planted by the French army. Two years pass in relative quiet, but at last the will for self-determination explodes through mass riots in the streets of Algiers that ultimately lead to Algeria winning its independence.

Pontecorvo recruited his actors from the streets of Algiers, including Brahim Haggiag, who would interpret his protagonist Ali La Pointe. Haggiag, an illiterate farmer that Pontecorvo discovered in an open-air market, has an intensity of expression that is perfectly suited to the young revolutionary. The only professional actor who performed in the film was Jean Martin, a little-known stage actor in France, who interpreted Colonel Matthieu. Jacef Saadi, one of the only FLN leaders taken alive during the struggle actually played himself, and Pontecorvo described him as resembling a young Paul Muni.

Pontecorvo also responded with great sensitivity to the city of Algiers and the spaces of the casbah. Scenes were conceived around the multi-tiered dwellings of the casbah with their courtyards and the sprawling honeycomb of moorish buildings before the commercial port. There is a magnificent sequence in which an Arab street cleaner tries to evade the police through the European quarter while pied noir Frenchmen villify him from their balconies. The Western façades appear out of place in this distinctly North African city.

The Battle of Algiers proved to be a great critical success, and secured Pontecorvo the Golden Lion at the Venice Festival and a second Academy Award nomination in 1967. Max Kozloff wondered if the film might prove a blueprint for revolt for underprivileged city dwellers in this country and The Battle of Algiers did pique the interest of members of the Black Panthers. In France the film was banned for one year following its release and bomb threats prevented cinema owners from screening the film for an additional four years. Finally, through an initiative taken by Louis Malle, The Battle of Algiers was screened in the Latin Quarter of Paris and French audiences began to appreciate its even handedness.

One of the interesting leitmotivs developed in the book is Pontecorvo’s love of music. In a 1972 interview with Piernico Solinas, Pontecorvo stated his pleasure at the comment made by a British film critic who declared, “But this is a musical!” after watching The Battle of Algiers. Pontecorvo’s family owned two pianos and as a child he learned to play by ear. Pontecorvo found himself in Paris in the late thirties where his brother Bruno was teaching at the Sorbonne. Pontecorvo and his circle of friends spent a great deal of time in a shop on boulevard Saint-Michel where, for a small fee, they could listen to music on headphones. The shopkeepers were anti-fascists and gave Pontecorvo the preferential treatment of allowing him to share his headphones with another person, which he did for reasons of economy. At the time he was very taken with La danse macabre of Saint-Saëns with its almost eastern musical phrases. His passion for music was born during the same period as his discovery of cinema.

Pontecorvo, after working as a courier between the French and Italian resistance, established himself in Milan as a “professional revolutionary” and Bignardi recounts an almost disturbing incident that took place during the summer of 1943. Milan was being bombed by the English, and Pontecorvo entered a flaming apartment to rescue his recording machine. I asked Pontecorvo what sort of relationship he had to Bach and he responded, “A relationship of dependence.” He used Saint Matthew’s Passion to great effect in The Battle of Algiers to describe the sense of grief and loss on the part of both French and Arab victims. He was to use the music of Bach in all the films of his maturity and Pontecorvo named his son Giovanni Sebastiano.

In a recent interview with the author, he described how a film never came alive for him until he had a sense of its music. The biography describes the difficulty Pontecorvo had with a scene from The Battle of Algiers in which Arab women make themselves up in the style of the French in order to pass unnoticed into the European quarter where they are going to plant bombs. Franco Solinas had written dialogue for the scene but Pontecorvo wasn’t convinced. At last, after various delays, he thought of baba saleem, drum music typically played by Algerian beggars that he had recorded. Its rhythm is close to that of the heartbeat, and baba saleem accompaniment greatly intensifies this scene that becomes entirely visual and musical. The melody that would become the Theme of Ali was composed by Pontecorvo and transcribed by Ennio Morricone while they were preparing the final cut of the film for the Venice Festival of 1966. Pontecorvo told me that visual images are not always the prevalent language of film, at times succumbing to music which conveys a deeper effect.

The biography describes work that Pontecorvo did to organize a strike in Turin during April 1945. The strike was viewed as a prelude to revolt and its goal was to involve as many people as possible. One incident, of which Pontecorvo was architect, involved stealing a truck that was equipped with a loudspeaker on the roof. Partisans recorded several minutes of music followed by a long revolutionary discourse on magnetic disc, and drove the truck into the center of town, near the German command. They started the music, which gave them ample time to flee, and then came a speech urging the people to revolt. This is very similar to a scene in The Battle of Algiers in which little Omar spirits the microphone away from a distracted French soldier and speaks words of encouragement to Algerians on strike.

Pontecorvo’s films express the necessity of armed revolt in the face of oppression, but they never seem dogmatic or insensitive to the complex issues of colonialism. It is the warmth and empathy of Pontecorvo for his subjects, on both sides of the political divide, that make his films so powerful. Irene Bignardi’s book is replete with information about Pontecorvo’s interests, passions, and obsessions that contribute to an appreciation of the gestalt of a film like The Battle of Algiers. Bignardi succeeds in conveying a sense of the fascination and complexity of Gillo Pontecorvo, his life, and his cinema of revolution.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2000.