Excerpts from an Interview with John Waters

John Waters exhibited twenty-six new photographic works in Straight to Video, an exhibition at American Fine Arts that ran through December 2000.

DKR – In your 1987 book Crackpot, you admonished filmakers to, “strive for art in reverse.” Could you elaborate on that statement in terms of your new photographs?

JW – Do I strive for art in reverse? Well in some ways. Anybody can take pictures off a television screen, so this work certainly isn’t about photography. It’s about editing really. It’s art work based on humor and editing and reading and what narrative is and how anything, even one second, can be narrative if its correctly displayed and titled. Much of the source material that I use failed in the movie business. It is the worst parts of my movies, the technical failures that work very well in the art world. So I guess that is art in reverse. Its a quote of mine that I barely remember saying. Its not one that’s often thrown in my face.

DKR – By working with sequential images and montage, you use the language of cinema even if there is no relationship between your photography and film projects.

JW – I use source material to reedit and redirect other images into my own. I think the work is least successful if people ask me, “what movie is that from?” If its successful it isn’t from any movie anymore. It has turned into my “movie.” I put that in quotes, they’re not movies, they’re to be shown in a gallery, and certainly not in a video presentation. That’s why I called the show Straight to Video. Probably “Straight From Video” would be more correct, but I just like the term “Straight to Video” because it’s critically almost the worst thing you can say about work. I try to live up to what is really the worst.

DKR – Why did you begin to make photographs?

JW – I wanted to steal from one of my movies that I never made. I wondered how I could do it. I wondered if photographs taken right off the tv screen would work and it did. Then I screwed up the negative and I tried to do it again, and you never can do it again exactly the same way. Its not digital, its not freeze frame, I just sit there in the dark and jump. Sometimes you see the tv in my shots, and I like that. I was so excited I missed. That’s how it started. I tried to get a still from my own movie that I didn’t make. Sometimes now I make a new kind of still. I did that whole other show called Marks at Gavin Brown’s gallery that was the opposite of film stills. They were film stills that showed only the marks where an actor had to hit (the only things you can’t show in a traditional film still). I took shots of the gaffer’s tape on the floor during the making of Pecker where the actor’s had to hit the mark.

DKR – There are levels of appropriation in this work. Sometimes you create hybrids between different Hollywood movies.

JW – I take from many levels of style and stardom, including my work, and putting them all together. I always make little narratives about things I like and sometimes I take them completely out of context and put them with other things and then they become a different story. In the Farrah Fawcett piece I just put Farrah hair on all the stars I like who have strong images to see how they’d look with a Farrah Fawcett hairdo. Two out of the six checkout girls in my supermarket have her hairdo, a major “Farrah” without any irony. So I thought this is what she has left to us. It should be bronzed in Baltimore. Most everyone in the world had a Farrah Fawcett hairdo.

DKR – The theme of censorship seems to be a leitmotif of your exhibition. Was Condemned born out of personal experiences with censorship?

JW – The nuns told me I would go to hell if I saw Baby Doll, which made me obsessed with it. Cardinal Sheehan, the Archbishop in New York, told everyone that they would go to hell if they saw the movie Baby Doll, so I wanted a picture of the condemned list. I went to the Catholic Review in Baltimore (which obviously is not a paper that would like me very much), but there was a woman there who is a photographer and a fan, and she let me into the files. I went back to the 50’s and found the condemned list of photographs, so that’s what it was about. The best piece that I made about censorship was the one with the asshole, you know the one with the curtain on it that you could close when your parents came home. I mean that was about censorship. That was from my second show at Collin de Land’s American Fine Arts, and there’s a whole little book just on that piece.

DKR – Buckle Up and Gore reflect your obsession with danger and violence. Could you tell me something about your interest in car accidents?

JW – Well I’m afraid I’ll die in a car accident. At least its glamorous to die in a plane accident. You’re going somewhere and there will be another celebrity on the plane, usually, if it’s international. My fear is dying in a car accident because its so low rent and so local. I don’t even look at car crashes because I think its going to happen to me. I was obsessed with car accidents as a child and my parents took me to a junkyard (they were very supportive of whatever my interests were). I remember looking at a car and seeing some blood on it and thinking, “oh my God, this is so great.” But the piece I did called Gore is a joke about sofa-size art. It’s the exact shape to go perfectly over a sofa, and I mean this is a piece that no one would put over their sofa. It has six or seven tiny little drops of blood from Herschell Lewis movies in deep detail, one tiny thing that was in the film for one fiftieth of a frame. I made it with children’s scissors because I was afraid to use good scissors because I’d cut myself, you know, and then there’d be more blood, and that would ruin it. At one time gore was a no no and it still horrifies people but cut out and isolated from everything and framed as if for decoration, it becomes almost beautiful to me.

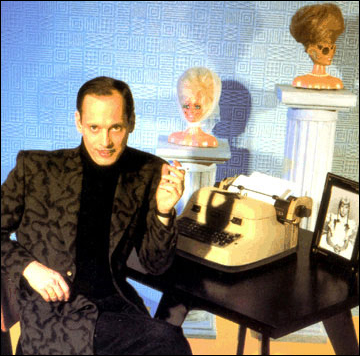

DKR – For Self Portrait #2 you seem to have created and photographed a mannequin of yourself. Could you discuss this experience of seeing yourself from without?

JW – Well actually it was a friend of mine named Joe Nero who made that John Waters doll for me. That was many years ago, and its been in my office where it’s fallen off the shelf twice and broken its nose. It originally smoked cigarettes, when I used to smoke, and it has a hole in its mouth where you put these little cigarettes and it puffed. To me it’s about marketing. You know they try to think up everything, but a movie company would never put out a John Waters doll because my films, even when successful, mock positive images for advertising. Basicly, to me, that piece was about the humor of marketing movies. It was seeing a John Waters doll that would never ever be manufactured. I look at it every day, its in my office, and I often photograph things that I’ve looked at for years but never taken a picture of or never looked at up close or out of context or in a narrative way. That’s how that piece came about.

DKR – Is there a story behind Rex Reed Gets Blowed?

JW – Rex Reed is probably the critic who has hated me the most for thirty years. At Christmas I wait for his negative review to come over the fax machine like a happy child on Christmas morning. So I figure, if I can take it all these years, he can take a little kidding back. But actually I think it is a handsome piece. I think the colors in it and everything are flattering to him. Maybe I didn’t mean it to be starting out, but I think its actually sexy and I never thought of Rex Reed getting blowed as a sexy image, at least for me. I’m sure it could be to some people.

DKR – My favorite piece in the exhibition is Retard, with its montage of actors ranging from Robert De Niro, Gerard Depardieu, and Mickey Rooney to Tom Hanks playing mentally retarded characters. How did you arrive at that montage of stills?

JW – They’ve all played it. It’s Oscar bait, and many of those photographs are from good performances and some aren’t, but basicly by playing a retarded person in a movie I think actors always lose ten years. When the movies come out people say, “weren’t they brave to play this, this is Oscar time here.” But they always look silly ten years later and all together these actors really look silly. It’s not a genre. Has there ever been a retarded film festival? You know its cinematically incorrect to even use the word “retard” but they all look like retards. The only great retarded movie is Idiots where they join this cult and go around stabbing people, I think that’s the best movie about fake retarded people ever.

DKR – There are numerous references to masks in your new photographs, from Swedish Film, in which sequential film stills document the removal of a rubber mask to Julia, in which Julia Robert’s smile is juxtaposed to the similar fixed smile of a burn victim. Could you discuss your interests in play-acting and the grotesque?

JW – I used to make Divine go see Ingmar Bergman movies with me when we were on LSD, and we were tripping during that scene where the woman rips her face off and it scared the shit out of us. It’s just a great memory and that’s why I put it in. It was from Hour of the Wolf or one of Bergman’s early black and white movies (of which I’m a huge fan). But that one moment has special, special meaning for me for many reasons. You hear that expression, “I’m going to rip her face off!” Well this woman did rip her face off but it was very unexpected. Divine used to hate me for taking him to these movies. He felt like seeing Elizabeth Taylor movies. He wasn’t really up for tripping and seeing an Ingmar Bergman movie, but this one worked because it was so shocking. I will always remember the wonderful moment on LSD when Ingmar Bergman really became an artist to me. I got the idea for the Julia Roberts piece (and I’m not trying to be mean to Julia Roberts), when I read this interview with her in which she said, “I look in the mirror and it looks like someone put a coat hanger in my mouth.” I remembered that interview and then I remembered this person who was a childhood hero of mine in a horror movie with that burned face and then I just put them together. Julia questions what is beauty and what is horror. The poster from the Apocalypse exhibition in London says “Beauty/ Horror” and its true because they’re really the same. Would Garbo be thought of as beautiful today? I don’t think so. She wouldn’t be thought of as ugly but I don’t think a girl who looked like her today would be a movie star. Beauty and horror are sometimes very very close.

© Daniel Rothbart, 2000.